Partners successfully compression mould parts using printed tooling

Thermwood and Purdue’s Composite Manufacturing & Simulation Center have been working together to develop and test methods of using 3D printed composite moulds for the compression moulding of thermoset parts.

Thermwood and Purdue’s Composite Manufacturing & Simulation Center have been working together to develop and test methods of using 3D printed composite moulds for the compression moulding of thermoset parts.

They have just announced that they have successfully been able to compression mould test parts using 3D printed composite tooling.

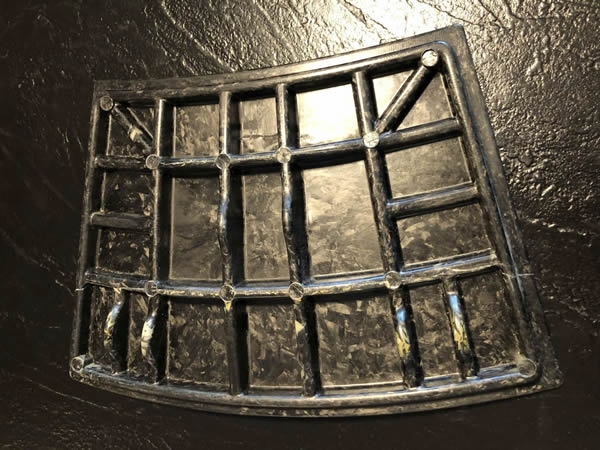

The test part, a half scale thrust reverser blocker door for a jet engine, was designed at Purdue and is approximately 10 x 13 x 2 inch in size. The two-part matched compression mould for the part was 3D printed using Techmer PM 25% carbon fibre reinforced PESU at Thermwood, using its LSAM large scale additive manufacturing system.

The mould halves were then machined to final size and shape on the same system. The completed tool was next taken to Purdue’s Composite Manufacturing & Simulation Center, in West Lafayette Indiana, where it was mounted to their 250tonne compression press. Parts were then moulded from Dow’s new Vorafuse prepreg platelet material system with over 50% carbon fibre volume fraction.

Machining, however, must be done in the traditional manner, one part at a time, although there is an advantage to machining printed parts. Since the part is printed to near net shape, the overall amount of material that must be removed is significantly less than if the tool was machined from a solid block. Machining of the two mould halves required an additional 27 hours.

The first attempt at compression moulding was not successful, but techniques were developed to account for the mechanical and thermal conductivity characteristics of the polymer print material and a second attempt produced acceptable parts.

A special heat control allows the temperature of various areas of the tool to be controlled independently, helping address the challenge of balancing the thermal characteristics of the thermoplastic composite mould with the processing temperature requirements of the thermoset material being processed.

Also, the outside of the mould must be reinforced so that the composite polymer used for the mould itself is under only compression loads and not tension during the moulding operation, since forces developed during moulding are greater than the tensile strength of the composite polymers used for the mould. This approach has successfully withstood moulding pressure of 1,500psi during initial testing and the team believes even higher pressures are possible.

Both Thermwood and Purdue believe this is an important first step in bringing additive manufacturing to compression moulding. The speed and relatively low cost of printed compression tools has the potential to significantly modify current industry practices. Printed tools are ideal for prototyping and can potentially avoid problems with long lead-time, expensive production tools by validating the design before a final version is built.

Potential applications in the auto industry include prototyping and production tool verification. Because of high volume requirements for auto production, it is unlikely that these tools would function adequately for full production use, but actual useful production life is still unknown. It will require additional testing to determine just how many parts can be moulded from an additive manufactured compression mould and what the ultimate failure mode actually is.

In aerospace, parts tend to be much larger and production volumes much lower, so it is possible that printed compression moulds could find actual production use for larger, lower volume aerospace components, perhaps replacing open face tools and autoclaves for certain parts.

The relatively low cost and fast build rate of these additive moulds significantly alters the decision matrix and timeline for developing new products using compression moulding.